The building Lab B occupies at 12-22 North Street was built in 1979/80 as a state-of-the-art passive solar demonstration project. With R-40+ wall insulation, a large brick thermal mass bisecting the building, and large arrays of south-facing windows on both the first and second floors, 12-22 gets and stays toasty in the winter.

While the front overhang helps a bit, it also gets toasty in the summer-time (particularly the southern offices), and we discovered just how toasty when the A/C unit died in the middle of July with no prospect of replacement until September. So, some hardcore kludging was in order…

To start, we immediately aimed to deploy a few portable air conditioners, but ran into to the fact that virtually all the windows are casement windows. So, the only kind of A/C that could work would be a portable one with a hose rather than a window unit, and we needed to figure out how to get the hose out with the remainder of the window sealed.

The best solution I found was a cloth adapter that attaches to either side of the window via adhesive velcro strips. In the center is a zipper with two pulls, so the exhaust tube can be zipped in and form a decent (but obviously not perfect) seal. One obvious downside is that it does not provide security, so for the window facing the street (rather than behind a fence) I ended up taking it down and closing the window at the end of each day. With the velcro, that was not a huge pain – once you have the hang of it, it’s maybe a minute to deploy, and less to break down.

The portable A/Cs took some of the edge off, but were clearly insufficient to get and keep the building at a comfortable temperature, particularly with “Earth’s Hottest Summer on Record” heat waves rolling in. So, in addition to our machines desperately pumping heat out of the building, we needed to figure out ways to minimize the heat coming into the building (“solar gain”).

The portable A/Cs took some of the edge off, but were clearly insufficient to get and keep the building at a comfortable temperature, particularly with “Earth’s Hottest Summer on Record” heat waves rolling in. So, in addition to our machines desperately pumping heat out of the building, we needed to figure out ways to minimize the heat coming into the building (“solar gain”).

The windows were already equipped with off-white cellular blinds which insulate and reflect a bit of heat, so my first addition was mounting some reflective bubble foil insulation to the interior of some windows, starting with the skylights. Being in a hurry, I simply used some loops of painters tape to adhere them to the skylights and some windows.

The windows were already equipped with off-white cellular blinds which insulate and reflect a bit of heat, so my first addition was mounting some reflective bubble foil insulation to the interior of some windows, starting with the skylights. Being in a hurry, I simply used some loops of painters tape to adhere them to the skylights and some windows.

This approach made a dent, but had two signficant flaws. First, no matter how reflective the material, once light passes into the building, a significant portion of the energy of the incoming light is captured as heat inside the building envelope. And said heat concentrated between the foil insulation and the window. With sufficient exposure to those high temperatures, the adhesive in the tape weakened and my sun-blocks gracefully fluttered to the floor within a matter of days.

A far superior approach is to intercept the solar heat before it enters the building envelope. The most common way of achieving this is with reflective film that is applied to the exterior of the window. However, as we didn’t want to give up the helpful solar gain in the Winter to mitigate our Summer suffering, we needed a more temporary solution that could be deployed when needed, and easily broken down and stored when not. One of the nicer options seems to be solar screens, but they were beyond both our current budget and time-frame – we required something that could arrive and be deployed quickly on a budget.

So, the first thing I decided to try was Aluminet. It’s a reflective woven material that comes in tarps, and is commonly used for shading crops in hot climates. You can order tarps that let various percentages of light through. I ordered two tarps that block 70% and let 30% through with different dimensions, and mounted them over some of the front windows. They seemed to be fairly effective, while still letting enough light through that the interior space didn’t feel gloomy. Another benefit that became apparent when I mounted a reflective solid tarp over another window to perform a similar function is aluminet’s relative resilience to high winds. When a thunder storm rolled through, the solid tarp became a kite that I had to go running after, while the holes in the aluminet meant the wind passed through and blowing away was never a problem.

So, the first thing I decided to try was Aluminet. It’s a reflective woven material that comes in tarps, and is commonly used for shading crops in hot climates. You can order tarps that let various percentages of light through. I ordered two tarps that block 70% and let 30% through with different dimensions, and mounted them over some of the front windows. They seemed to be fairly effective, while still letting enough light through that the interior space didn’t feel gloomy. Another benefit that became apparent when I mounted a reflective solid tarp over another window to perform a similar function is aluminet’s relative resilience to high winds. When a thunder storm rolled through, the solid tarp became a kite that I had to go running after, while the holes in the aluminet meant the wind passed through and blowing away was never a problem.

A second affordable/DIY exterior mounted solution I came across found me reusing the sheets of bubble foil insulation that had fallen from the skylights earlier. The core idea is simple: add suction cups to the corners and stick them on the window exterior. After ordering a professionally manufactured version with a few week lead-time for under $20, I scrounged up some used suction cups to make a few (less attractive) DIY versions for immediate deployment. I only made them about half of the height of the window, as the top portion tends the be shaded by the overhang, and so they would block most of the heat while still allowing natural light into the offices.

A second affordable/DIY exterior mounted solution I came across found me reusing the sheets of bubble foil insulation that had fallen from the skylights earlier. The core idea is simple: add suction cups to the corners and stick them on the window exterior. After ordering a professionally manufactured version with a few week lead-time for under $20, I scrounged up some used suction cups to make a few (less attractive) DIY versions for immediate deployment. I only made them about half of the height of the window, as the top portion tends the be shaded by the overhang, and so they would block most of the heat while still allowing natural light into the offices.

As they accumulated, the exterior interventions made a meaningful dent on the solar gain, and gave our long-suffering portable A/C units the breathing room they needed to keep the building mostly comfortable.

With the arrival of the 45 degree nights of Vermont’s Fall, the urgency of this work has begun to fade, and installation of the building’s new heat pump has begun, so the end of the crisis period is in sight. However, the motivation of avoiding an 80+ degree office ended up teaching me a lot about the dynamics of solar gain. It also provided ideas for annual interventions (such as obtaining a full complement of the professional suction cup-mounted window coverings) that will, complementing the new HVAC, allow the building to operate far more efficiently in the coming (ever hotter) Summers.

Stay Cool!

During this quick 4 hour class students will learn how to build a Pirate Box. This class will guide students through the process of converting a plain TP-Link MR3020 and USB thumb drive into a Pirate Box.

During this quick 4 hour class students will learn how to build a Pirate Box. This class will guide students through the process of converting a plain TP-Link MR3020 and USB thumb drive into a Pirate Box.

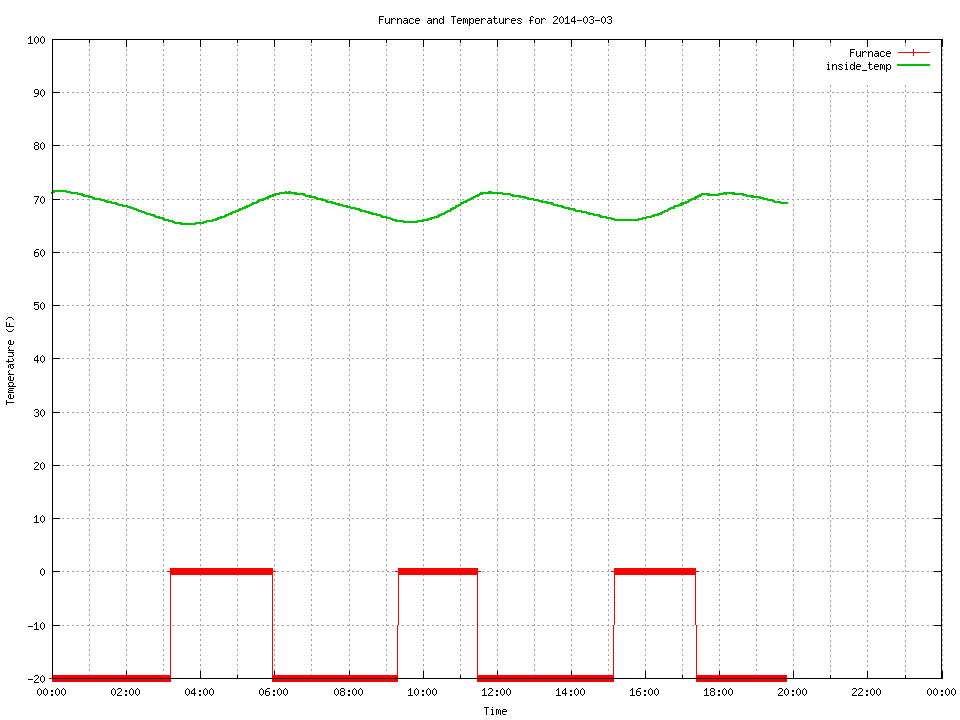

![show_graph_2014-10-11.cgi_[1]](https://www.laboratoryb.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/show_graph_2014-10-11.cgi_1-300x225.png)

![Photo-Oct-14-15-20-27[1]](https://www.laboratoryb.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Photo-Oct-14-15-20-271-180x300.jpg)

![show_graph_2014-10-13.cgi_[1]](https://www.laboratoryb.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/show_graph_2014-10-13.cgi_1-300x225.png)